HOUSING HISTORIES: AUTOCONSTRUCTION AND ARCHITECTURE IN BENEDICT CANYON [2025]

[UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SANTA BARBARA: ART HISTORY GRADUATE STUDENT ASSOCIATION (AHGSA) GRADUATE STUDENT SYMPOSIUM]

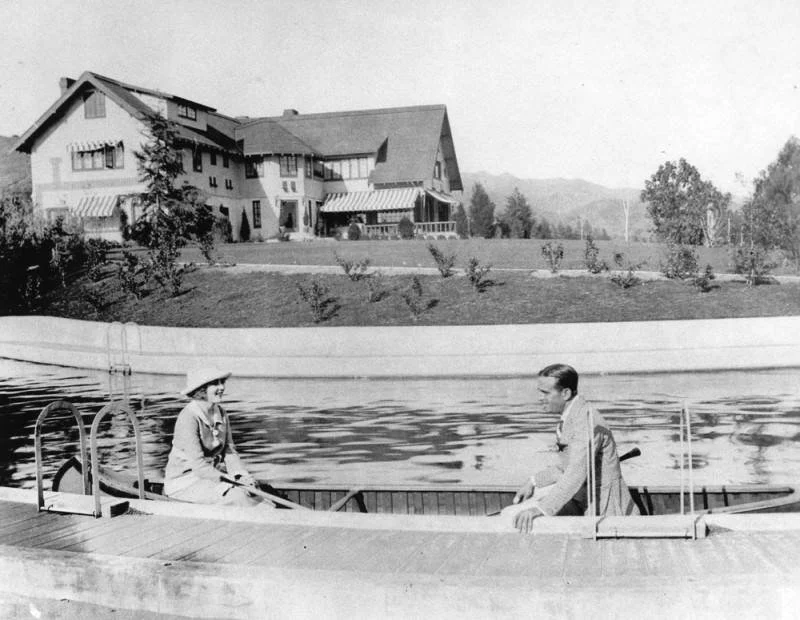

In a 2021 retrospective of Wallace Neff’s long and prolific career as a residential architect, historian Eleanor Schrader praised him for “[his] ability to combine Spanish, Tuscan, Mediterranean, Islamic, and other design elements […] seamlessly into something he called ‘The California Style.’” In the 1920s and 1930s Neff gained recognition for his celebrity commissions—including but not limited to Pickfair, a mansion for actors Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks; Misty Mountain, a mansion for film director Fred Niblo and actress Enid Bennett; the Vidor King and Eleanor Boardman House; and the Fredric March House. All of these residences were once located in the picturesque Benedict Canyon, a luxury Beverly Hills neighborhood with mature trees and winding streets. Some were “inspired by Mediterranean architecture;” others “included elements from French and English vernacular.” Yet, architectural historians agree that all embody the “place and tradition” of Southern California: While the Mission, Spanish, and Mediterranean design features reflect the modern landscape of the region, the English Cotswold, French Norman, and New Englander design features reflect the traditional image of the nation.

Benedict Canyon’s premier status as a “Southland” celebrity enclave belies its humble origin as an American homesteading colony: In the 1920s and 1930s its lots sold for thousands of dollars per acre, but in the 1860s and 1870s its lands were so “valueless” and “scattered” that the federal government gave them away for free. The Art, Design & Architecture Museum at the University of California Santa Barbara hosts an archive of Neff’s work, which is integral to Southern California’s canon—a canon shaped more by the industrial wealth of Hollywood elites than by the agricultural enterprise of migrant workers. Yet, Benedict Canyon was named by and for Edson Abijah Benedict (1819–1886), an American farmer whose family settled there in 1868 and remained there until 1928. Photographs of his and his neighbors’ autoconstructed houses may or may not exist, but descriptions and maps of them certainly do. This article uses these descriptions and maps to reconstruct and recenter Benedict Canyon’s earliest residences not only in Southern California’s architectural history but also in the United States’ colonial history. It argues that although these residences were designed and built by and for non-professionals, they, too, are integral to the region’s—and the nation’s—turn-of-the-century imaginary.